Any onetime Mafia investigator who listened to Donald Trump “fixer” Michael Cohen testify Wednesday would have immediately recognized the congressional hearing’s historical analogue — what America witnessed on Capitol Hill wasn’t so much John Dean turning on President Richard Nixon, circa 1973; it was the mobster Joseph Valachi turning on the Cosa Nostra, circa 1963.

The Valachi hearings, led by Senator John McClellan of Arkansas, opened the country’s eyes for the first time to the Mafia, as the witness broke “omertà” — the code of silence — to speak in public about “this thing of ours,” Cosa Nostra. He explained just how “organized” organized crime actually was — with soldiers, capos, godfathers and even the “Commission,” the governing body of the various Mafia families.

Fighting the Mafia posed a uniquely hard challenge for investigators. Mafia families were involved in numerous distinct crimes and schemes, over yearslong periods, all for the clear benefit of its leadership, but those very leaders were tough to prosecute because they were rarely involved in the day-to-day crime. They spoke in their own code, rarely directly ordering a lieutenant to do something illegal, but instead offering oblique instructions or expressing general wishes that their lieutenants simply knew how to translate into action.

Those explosive — and arresting — hearings led to the 1970 passage of the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act, better known as RICO, a law designed to allow prosecutors to go after enterprises that engaged in extended, organized criminality. RICO laid out certain “predicate” crimes — those that prosecutors could use to stitch together evidence of a corrupt organization and then go after everyone involved in the organization as part of an organized conspiracy. While the headline-grabbing RICO “predicates” were violent crimes like murder, kidnapping, arson and robbery, the statute also focused on crimes like fraud, obstruction of justice, money laundering and even aiding or abetting illegal immigration.

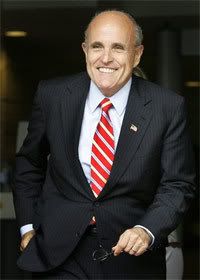

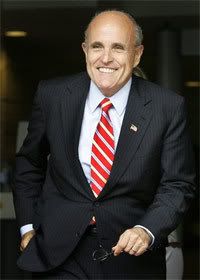

It took prosecutors a while to figure out how to use RICO effectively, but by the mid-1980s, federal investigators in the Southern District of New York were hitting their stride under none other than the crusading United States attorney Rudy Giuliani, who as the head of the Southern District brought charges in 1985 against the heads of the city’s five dominant Mafia families.

Ever since, S.D.N.Y. prosecutors and F.B.I. agents have been the nation’s gold standard in RICO prosecutions — a fact that makes clear precisely why, after Mr. Cohen’s testimony, President Trump’s greatest legal jeopardy may not be in the investigation by the special counsel, Robert Mueller.

What lawmakers heard Wednesday sounded a lot like a racketeering enterprise: an organization with a few key players and numerous overlapping crimes — not just one conspiracy, but many. Even leaving aside any questions about the Mueller investigation and the 2016 campaign, Mr. Cohen leveled allegations that sounded like bank fraud, charity fraud and tax fraud, as well as hints of insurance fraud, obstruction of justice and suborning perjury.

The parallels between the Mafia and the Trump Organization are more than we might like to admit: After all, Mr. Cohen was labeled a “rat” by President Trump last year for agreeing to cooperate with investigators; interestingly, in the language of crime, “rats” generally aren’t seen as liars. They’re “rats” precisely because they turn state’s evidence and tell the truth, spilling the secrets of a criminal organization.

Mr. Cohen was clear about the rot at the center of his former employer: “Everybody’s job at the Trump Organization is to protect Mr. Trump. Every day most of us knew we were coming and we were going to lie for him about something. That became the norm.”

RICO was precisely designed to catch the godfathers and bosses at the top of these crime syndicates — people a step or two removed from the actual crimes committed, those whose will is made real, even without a direct order.

Exactly, it appears, as Mr. Trump did at the top of his family business: “Mr. Trump did not directly tell me to lie to Congress. That’s not how he operates,” Mr. Cohen said. Mr. Trump, Mr. Cohen said, “doesn’t give orders. He speaks in code. And I understand that code.”

What’s notable about Mr. Cohen’s comments is how they paint a consistent (and credible) pattern of Mr. Trump’s behavior: The former F.B.I. director James Comey, in testimony nearly two years ago in the wake of his firing, made almost exactly the same point and used almost exactly the same language. Mr. Trump never directly ordered him to drop the Flynn investigation, Mr. Comey said, but he made it all too clear what he wanted — the president isolated Mr. Comey, with no other ears around, and then said he hoped Mr. Comey “can let this go.” As Mr. Comey said, “I took it as, this is what he wants me to do.” He cited in his testimony then the famous example of King Henry II’s saying, “Will no one rid me of this turbulent priest?,” a question that resulted in the murder of that very meddlesome priest, Thomas Becket.

The sheer number and breadth of the investigations into Mr. Trump’s orbit these days indicates how vulnerable the president’s family business would be to just this type of prosecution. In December, I counted 17, and since then, investigators have started an inquiry into undocumented workers at Mr. Trump’s New Jersey golf course, another crime that could be a RICO predicate; Mr. Cohen’s public testimony itself, where he certainly laid out enough evidence and bread crumbs for prosecutors to verify his allegations, mentioned enough criminal activity to build a racketeering case. Moreover, RICO allows prosecutors to wrap 10 years of racketeering activity into a single set of charges, which is to say, almost precisely the length of time — a decade — that Michael Cohen would have unparalleled insight into Mr. Trump’s operations. Similarly, many Mafia cases end up being built on wiretaps — just like, for instance, the perhaps 100 recordings Mr. Cohen says he made of people during his tenure working for Mr. Trump, recordings that federal investigators are surely poring over as part of the 290,000 documents and files they seized in their April raid last year.

Indicting the whole Trump Organization as a “corrupt enterprise” could also help prosecutors address the thorny question of whether the president can be indicted in office; they could lay out a whole pattern of criminal activity, indict numerous players — including perhaps Trump family members — and leave the president himself as a named, unindicted co-conspirator. Such an action would allow investigators to make public all the known activity for Congress and the public to consider as part of impeachment hearings or re-election. It would also activate powerful forfeiture tools for prosecutors that could allow them to seize the Trump Organization’s assets and cut off its income streams.

The irony will be that if federal prosecutors decide to move against President Trump’s empire and family together, he’ll have one man’s model to thank: his own TV lawyer, Rudy Giuliani, who perfected the template to tackle precisely that type of criminal enterprise.

Thanks to Garrett M. Graff.

Get the latest breaking current news and explore our Historic Archive of articles focusing on The Mafia, Organized Crime, The Mob and Mobsters, Gangs and Gangsters, Political Corruption, True Crime, and the Legal System at TheChicagoSyndicate.com

Tuesday, March 05, 2019

Mob Hit on Rudy Giuilani Discussed

The bosses of New York's five Cosa Nostra families discussed killing then-federal prosecutor Rudy Giuliani  in 1986, an informant told the FBI, according to testimony in October of 2007, in Brooklyn state court. But while the late Gambino crime boss John Gotti pushed the idea, he only had the support of Carmine Persico, the leader of the Colombo crime family, according to the testimony.

in 1986, an informant told the FBI, according to testimony in October of 2007, in Brooklyn state court. But while the late Gambino crime boss John Gotti pushed the idea, he only had the support of Carmine Persico, the leader of the Colombo crime family, according to the testimony.

"The Bosses of the Luchese, Bonanno and Genovese families rejected the idea, despite strong efforts to convince them otherwise by Gotti and Persico," said an FBI report of the information given by informant Gregory Scarpa Sr.

Information about the purported murder plot was given to the FBI in 1987 by Scarpa, a Colombo captain, according to the testimony of FBI agent William Bolinder in State Supreme Court in Brooklyn.

Bolinder was testifying as a prosecution witness in the murder trial of ex-FBI agent Roy Lindley DeVecchio, who handled the now deceased Scarpa for years while the mobster was a key informant. Prosecutors contend that DeVecchio passed information to Scarpa that the mobster used in killings.

In his testimony, Bolinder described the contents of a voluminous FBI file on Scarpa, who died of AIDS in 1994.

In September 1987, DeVecchio reported that Scarpa told him that the five mob families talked about killing Giuliani approximately a year earlier, said Bolinder. It was in September 1986 that Giuliani's staff at the Manhattan U.S. attorney's office prosecuted bosses of La Cosa Nostra families in the so-called "Commission" case.

The Commission trial, a springboard for Giuliani's reputation as a crime buster, resulted in the conviction in October 1986 of Colombo boss Carmine Persico, Lucchese boss Anthony Corallo and Genovese street boss Anthony Salerno. Gambino boss Paul Castellano was assassinated in December 1985 and the case against Bonanno boss Philip Rastelli was dropped.

The purported discussion about murdering Giuliani wasn't the first time he was targeted. In an interview in 1985 Giuliani stated that Albanian drug dealers plotted to kill him and two other officials. A murder contract price of $400,000 was allegedly offered by convicted heroin dealer Zhevedet Lika for the deaths of prosecutor Alan Cohen and DEA agent Jack Delmore, said Giuliani. Neither Cohen nor Delmore were harmed.

Other tidbits offered by Scarpa to DeVecchio involved an allegation of law enforcement corruption within the Brooklyn district attorney's office, said Bolinder. In 1983, stated Bolinder, Scarpa reported that an NYPD detective assigned to the Brooklyn district attorney's office (then led by Elizabeth Holtzman) had been taking money to leak information to the Gambino and Colombo families. A spokesman for current Brooklyn District Attorney Charles J. Hynes said no investigation was ever done about the allegation.

Scarpa also reported to DeVecchio that top Colombo crime bosses suspected the Casa Storta restaurant in Brooklyn was bugged because FBI agents never surveilled the mobsters when they met there. The restaurant was in fact bugged, government records showed.

Thanks to Anthony M. Destefano

in 1986, an informant told the FBI, according to testimony in October of 2007, in Brooklyn state court. But while the late Gambino crime boss John Gotti pushed the idea, he only had the support of Carmine Persico, the leader of the Colombo crime family, according to the testimony.

in 1986, an informant told the FBI, according to testimony in October of 2007, in Brooklyn state court. But while the late Gambino crime boss John Gotti pushed the idea, he only had the support of Carmine Persico, the leader of the Colombo crime family, according to the testimony."The Bosses of the Luchese, Bonanno and Genovese families rejected the idea, despite strong efforts to convince them otherwise by Gotti and Persico," said an FBI report of the information given by informant Gregory Scarpa Sr.

Information about the purported murder plot was given to the FBI in 1987 by Scarpa, a Colombo captain, according to the testimony of FBI agent William Bolinder in State Supreme Court in Brooklyn.

Bolinder was testifying as a prosecution witness in the murder trial of ex-FBI agent Roy Lindley DeVecchio, who handled the now deceased Scarpa for years while the mobster was a key informant. Prosecutors contend that DeVecchio passed information to Scarpa that the mobster used in killings.

In his testimony, Bolinder described the contents of a voluminous FBI file on Scarpa, who died of AIDS in 1994.

In September 1987, DeVecchio reported that Scarpa told him that the five mob families talked about killing Giuliani approximately a year earlier, said Bolinder. It was in September 1986 that Giuliani's staff at the Manhattan U.S. attorney's office prosecuted bosses of La Cosa Nostra families in the so-called "Commission" case.

The Commission trial, a springboard for Giuliani's reputation as a crime buster, resulted in the conviction in October 1986 of Colombo boss Carmine Persico, Lucchese boss Anthony Corallo and Genovese street boss Anthony Salerno. Gambino boss Paul Castellano was assassinated in December 1985 and the case against Bonanno boss Philip Rastelli was dropped.

The purported discussion about murdering Giuliani wasn't the first time he was targeted. In an interview in 1985 Giuliani stated that Albanian drug dealers plotted to kill him and two other officials. A murder contract price of $400,000 was allegedly offered by convicted heroin dealer Zhevedet Lika for the deaths of prosecutor Alan Cohen and DEA agent Jack Delmore, said Giuliani. Neither Cohen nor Delmore were harmed.

Other tidbits offered by Scarpa to DeVecchio involved an allegation of law enforcement corruption within the Brooklyn district attorney's office, said Bolinder. In 1983, stated Bolinder, Scarpa reported that an NYPD detective assigned to the Brooklyn district attorney's office (then led by Elizabeth Holtzman) had been taking money to leak information to the Gambino and Colombo families. A spokesman for current Brooklyn District Attorney Charles J. Hynes said no investigation was ever done about the allegation.

Scarpa also reported to DeVecchio that top Colombo crime bosses suspected the Casa Storta restaurant in Brooklyn was bugged because FBI agents never surveilled the mobsters when they met there. The restaurant was in fact bugged, government records showed.

Thanks to Anthony M. Destefano

Related Headlines

Anthony Corallo,

Carmine Persico,

Greg Scarpa Sr.,

John Gotti,

Lin DeVecchio,

Paul Castellano,

Philip Rastelli,

Rudy Giuliani,

Tony Salerno

1 comment:

Wednesday, February 27, 2019

John Matassa, Longtime Union Boss and Reputed Mob Figure Pleads Guilty to Embezzlement

A reputed Chicago mob figure and longtime union boss pleaded guilty Tuesday to a federal felony charge of embezzlement in an alleged scheme to fraudulently qualify for early retirement benefits.

John Matassa Jr., 67, known by the nickname “Pudgy,” faces up to about 21 months in prison after entering his plea on the lone count before U.S. District Judge Matthew Kennelly, according to a plea agreement with prosecutors.

"The guy's hanging on to the carpet like a cat," one union member told the Tribune at the time. "He's just not cooperating at all. I just can't wait until he's gone."

Matassa’s name also surfaced during the 2009 trial of a deputy U.S. marshal who was convicted of leaking sensitive information to a family friend with alleged mob ties, knowing the details would end up in the Outfit's hands. Matassa allegedly acted as a go-between.

The leak involved the then-secret cooperation of Outfit turncoat Nicholas Calabrese, whose testimony led to the convictions of numerous mob figures — including Marcello — in the landmark Operation Family Secrets investigation.

Calabrese testified at the Family Secrets trial that Matassa was present in October 1983 when Calabrese was indoctrinated as a “made” member of the mob at a ceremony at a shuttered restaurant on Mannheim Road.

Matassa, the former secretary-treasurer of the Independent Union of Amalgamated Workers Local 711, was charged in a 10-count indictment in 2017 with putting his wife on the union’s payroll in a do-nothing job while lowering his own salary.

He then applied for early retirement benefits from the Social Security Administration's Old-Age Insurance program, listing his reduced salary to qualify for those benefits, the indictment alleged.

The charges also alleged that Matassa personally signed his wife's paychecks from the union over a four-year period and had them deposited into the couple's bank account.

According to Matassa’s 18-page plea agreement, preliminary sentencing calculations call for him to be given 15 to 21 months in prison, but Kennelly will make the final decision. Matassa must also pay a total of $66,500 in restitution to the union and Social Security Administration, according to the agreement.

Kennelly set sentencing for May 22.

Dressed in a purple checkered shirt, the husky Matassa, of Arlington Heights, leaned against a lectern and answered, “Yes, your honor” in a deep voice as Kennelly asked him if he understood the terms of his plea deal. About halfway thought the 40-minute hearing, Matassa accepted the judge’s offer and took a seat.

For years, Matassa has been associated with some of the Outfit’s most notorious figures, including former reputed boss James “Jimmy Light” Marcello.

In the late 1990s, Matassa was kicked out as president of the Laborers Union Chicago local over his alleged extensive ties to organized crime — a move Matassa fought for years.

"The guy's hanging on to the carpet like a cat," one union member told the Tribune at the time. "He's just not cooperating at all. I just can't wait until he's gone."

Matassa’s name also surfaced during the 2009 trial of a deputy U.S. marshal who was convicted of leaking sensitive information to a family friend with alleged mob ties, knowing the details would end up in the Outfit's hands. Matassa allegedly acted as a go-between.

The leak involved the then-secret cooperation of Outfit turncoat Nicholas Calabrese, whose testimony led to the convictions of numerous mob figures — including Marcello — in the landmark Operation Family Secrets investigation.

Calabrese testified at the Family Secrets trial that Matassa was present in October 1983 when Calabrese was indoctrinated as a “made” member of the mob at a ceremony at a shuttered restaurant on Mannheim Road.

Thanks to Jason Meisner.

John Matassa Jr., 67, known by the nickname “Pudgy,” faces up to about 21 months in prison after entering his plea on the lone count before U.S. District Judge Matthew Kennelly, according to a plea agreement with prosecutors.

"The guy's hanging on to the carpet like a cat," one union member told the Tribune at the time. "He's just not cooperating at all. I just can't wait until he's gone."

Matassa’s name also surfaced during the 2009 trial of a deputy U.S. marshal who was convicted of leaking sensitive information to a family friend with alleged mob ties, knowing the details would end up in the Outfit's hands. Matassa allegedly acted as a go-between.

The leak involved the then-secret cooperation of Outfit turncoat Nicholas Calabrese, whose testimony led to the convictions of numerous mob figures — including Marcello — in the landmark Operation Family Secrets investigation.

Calabrese testified at the Family Secrets trial that Matassa was present in October 1983 when Calabrese was indoctrinated as a “made” member of the mob at a ceremony at a shuttered restaurant on Mannheim Road.

Matassa, the former secretary-treasurer of the Independent Union of Amalgamated Workers Local 711, was charged in a 10-count indictment in 2017 with putting his wife on the union’s payroll in a do-nothing job while lowering his own salary.

He then applied for early retirement benefits from the Social Security Administration's Old-Age Insurance program, listing his reduced salary to qualify for those benefits, the indictment alleged.

The charges also alleged that Matassa personally signed his wife's paychecks from the union over a four-year period and had them deposited into the couple's bank account.

According to Matassa’s 18-page plea agreement, preliminary sentencing calculations call for him to be given 15 to 21 months in prison, but Kennelly will make the final decision. Matassa must also pay a total of $66,500 in restitution to the union and Social Security Administration, according to the agreement.

Kennelly set sentencing for May 22.

Dressed in a purple checkered shirt, the husky Matassa, of Arlington Heights, leaned against a lectern and answered, “Yes, your honor” in a deep voice as Kennelly asked him if he understood the terms of his plea deal. About halfway thought the 40-minute hearing, Matassa accepted the judge’s offer and took a seat.

For years, Matassa has been associated with some of the Outfit’s most notorious figures, including former reputed boss James “Jimmy Light” Marcello.

In the late 1990s, Matassa was kicked out as president of the Laborers Union Chicago local over his alleged extensive ties to organized crime — a move Matassa fought for years.

"The guy's hanging on to the carpet like a cat," one union member told the Tribune at the time. "He's just not cooperating at all. I just can't wait until he's gone."

Matassa’s name also surfaced during the 2009 trial of a deputy U.S. marshal who was convicted of leaking sensitive information to a family friend with alleged mob ties, knowing the details would end up in the Outfit's hands. Matassa allegedly acted as a go-between.

The leak involved the then-secret cooperation of Outfit turncoat Nicholas Calabrese, whose testimony led to the convictions of numerous mob figures — including Marcello — in the landmark Operation Family Secrets investigation.

Calabrese testified at the Family Secrets trial that Matassa was present in October 1983 when Calabrese was indoctrinated as a “made” member of the mob at a ceremony at a shuttered restaurant on Mannheim Road.

Thanks to Jason Meisner.

Tuesday, February 26, 2019

Lawyer for Joseph Cammarano Jr, Reputed Acting Boss of Bonanno Crime Family: Looking like a mobster doesn't mean he's guilty!

An alleged mafia boss in New York City should not be convicted just because he looks like a mobster, his attorney has said.

Joseph Cammarano Jr, who is said to be acting boss of New York's Bonanno crime syndicate, faces up to 40 years in prison on racketeering charges.

Cammarano, 59, appeared in court with slicked-back hair, a spotted suit and a silver ring. But his lawyer, Jennifer Louis-Jeune, pleaded with jurors to ignore his 'central casting' appearance, the New York Post reported.

She told the federal court in Manhattan: 'Looking like you stepped out of a central casting in a mob movie doesn’t make you a part of one of these groups. 'Don’t be distracted. Don’t let what you have seen in movies or on TV or whatever you have heard about the mafia cloud your judgement.'

Asked if he looked like a gang boss, Cammarano joked: 'No, but I've got the map of Italy on my face'.

Prosecutors told the court in their opening statement that Cammarano had committed 'crime after crime'.

Another former Bonanno mafia member gave evidence for the prosecution, telling jurors about a meeting where Cammarano had been chosen as the new boss.

Cammarano was one of 10 people indicted last year for their alleged links to the New York crime syndicate, although many of them have since accepted plea deals.

The Bonanno ring is one of the so-called Five Families which dominate organized crime in the city.

The indictment also listed the gang's colorful nicknames including 'Joe C' for Cammarano and other members including 'Grumpy', 'Porky' and 'Joey Blue Eyes'.

Cammarano himself is accused of being the 'acting boss' of the Bonanno crime gang.

Thanks to Tim Stickings.

Joseph Cammarano Jr, who is said to be acting boss of New York's Bonanno crime syndicate, faces up to 40 years in prison on racketeering charges.

Cammarano, 59, appeared in court with slicked-back hair, a spotted suit and a silver ring. But his lawyer, Jennifer Louis-Jeune, pleaded with jurors to ignore his 'central casting' appearance, the New York Post reported.

She told the federal court in Manhattan: 'Looking like you stepped out of a central casting in a mob movie doesn’t make you a part of one of these groups. 'Don’t be distracted. Don’t let what you have seen in movies or on TV or whatever you have heard about the mafia cloud your judgement.'

Asked if he looked like a gang boss, Cammarano joked: 'No, but I've got the map of Italy on my face'.

Prosecutors told the court in their opening statement that Cammarano had committed 'crime after crime'.

Another former Bonanno mafia member gave evidence for the prosecution, telling jurors about a meeting where Cammarano had been chosen as the new boss.

Cammarano was one of 10 people indicted last year for their alleged links to the New York crime syndicate, although many of them have since accepted plea deals.

The Bonanno ring is one of the so-called Five Families which dominate organized crime in the city.

The indictment also listed the gang's colorful nicknames including 'Joe C' for Cammarano and other members including 'Grumpy', 'Porky' and 'Joey Blue Eyes'.

Cammarano himself is accused of being the 'acting boss' of the Bonanno crime gang.

Thanks to Tim Stickings.

Thursday, February 14, 2019

The Untold Story of the Gangland Bloodbath That Brought Down Al Capone

Thanks to Art Bilek for sharing with us a deep account for the St. Valentine's Day Massacre. It will make a nice addition to any Mobologist's library: The St. Valentine's Day Massacre: The Untold Story of the Gangland Bloodbath That Brought Down Al Capone.

During Prohibition , Chicago’s Beer Wars turned the city into a battleground, secured its reputation as gangster capital of the world, and laid the foundation for nationally organized crime. Bootlegger bloodshed was greater there than anywhere else.

, Chicago’s Beer Wars turned the city into a battleground, secured its reputation as gangster capital of the world, and laid the foundation for nationally organized crime. Bootlegger bloodshed was greater there than anywhere else.

The machine-gun murders of seven men on the morning of February 14, 1929, by killers dressed as cops became the gangland "crime of the century." Since then it has been featured in countless histories, biographies, movies, and television specials. The St. Valentine’s Day Massacre, however, is the first book-length treatment of the subject. Unlike other accounts, it challenges the commonly held assumption that Al Capone decreed the slayings to gain supremacy in the Chicago underworld. The authors assert the deed was a case of bad timing and poor judgment by a secret crew from St. Louis known to Capone’s mostly Italian mob as the "American boys."

The target of the murder squad was indeed Bugs Moran, but the "American boys," who were dressed as policemen and arrived in two bogus police cars, arrived early at the garage where the massacre took place. When no one in the garage would admit he was Bugs Moran, the bogus cops stupidly killed them all. Much of the evidence to this effect emerged shortly after the massacre but was deftly ignored by law enforcement officials. It began to resurface again in 1935 with a manuscript written by the widow of one of the gunmen and a lookout’s long-suppressed confession. Indeed, law enforcement tried very hard not to solve the crime, for under any rock the cops turned over there might be a politician, and under the St. Valentine’s Day rock they would have found several. In the end, the machine gun bullets heard ’round the world marked the beginning of the end for Al Capone.

During Prohibition

, Chicago’s Beer Wars turned the city into a battleground, secured its reputation as gangster capital of the world, and laid the foundation for nationally organized crime. Bootlegger bloodshed was greater there than anywhere else.

, Chicago’s Beer Wars turned the city into a battleground, secured its reputation as gangster capital of the world, and laid the foundation for nationally organized crime. Bootlegger bloodshed was greater there than anywhere else.The machine-gun murders of seven men on the morning of February 14, 1929, by killers dressed as cops became the gangland "crime of the century." Since then it has been featured in countless histories, biographies, movies, and television specials. The St. Valentine’s Day Massacre, however, is the first book-length treatment of the subject. Unlike other accounts, it challenges the commonly held assumption that Al Capone decreed the slayings to gain supremacy in the Chicago underworld. The authors assert the deed was a case of bad timing and poor judgment by a secret crew from St. Louis known to Capone’s mostly Italian mob as the "American boys."

The target of the murder squad was indeed Bugs Moran, but the "American boys," who were dressed as policemen and arrived in two bogus police cars, arrived early at the garage where the massacre took place. When no one in the garage would admit he was Bugs Moran, the bogus cops stupidly killed them all. Much of the evidence to this effect emerged shortly after the massacre but was deftly ignored by law enforcement officials. It began to resurface again in 1935 with a manuscript written by the widow of one of the gunmen and a lookout’s long-suppressed confession. Indeed, law enforcement tried very hard not to solve the crime, for under any rock the cops turned over there might be a politician, and under the St. Valentine’s Day rock they would have found several. In the end, the machine gun bullets heard ’round the world marked the beginning of the end for Al Capone.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

The Prisoner Wine Company Corkscrew with Leather Pouch

Best of the Month!

- Mafia Wars Move to the iPhone World

- The Chicago Syndicate AKA "The Outfit"

- Chicago Mob Infamous Locations Map

- Mob Hit on Rudy Giuilani Discussed

- Mob Murder Suggests Link to International Drug Ring

- Chicago Outfit Mob Etiquette

- Top Mobster Nicknames

- Bonanno Crime Family

- Tokyo Joe: The Man Who Brought Down the Chicago Mob (Mafia o Utta Otoko)

- Was Jimmy Hoffa Killed by Frank "The Irishman" Sheeran