Any onetime Mafia investigator who listened to

Donald Trump “fixer”

Michael Cohen testify Wednesday would have immediately recognized the congressional hearing’s historical analogue — what America witnessed on Capitol Hill wasn’t so much John Dean turning on

President Richard Nixon, circa 1973; it was the mobster

Joseph Valachi turning on the Cosa Nostra, circa 1963.

The Valachi hearings, led by Senator John McClellan of Arkansas, opened the country’s eyes for the first time to the Mafia, as the witness broke “omertà” — the code of silence — to speak in public about “this thing of ours,”

Cosa Nostra. He explained just how “organized” organized crime actually was — with soldiers, capos, godfathers and even the “Commission,” the governing body of the various Mafia families.

Fighting the Mafia posed a uniquely hard challenge for investigators. Mafia families were involved in numerous distinct crimes and schemes, over yearslong periods, all for the clear benefit of its leadership, but those very leaders were tough to prosecute because they were rarely involved in the day-to-day crime. They spoke in their own code, rarely directly ordering a lieutenant to do something illegal, but instead offering oblique instructions or expressing general wishes that their lieutenants simply knew how to translate into action.

Those explosive — and arresting — hearings led to the 1970 passage of the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act, better known as RICO, a law designed to allow prosecutors to go after enterprises that engaged in extended, organized criminality. RICO laid out certain “predicate” crimes — those that prosecutors could use to stitch together evidence of a corrupt organization and then go after everyone involved in the organization as part of an organized conspiracy. While the headline-grabbing RICO “predicates” were violent crimes like murder, kidnapping, arson and robbery, the statute also focused on crimes like fraud, obstruction of justice, money laundering and even aiding or abetting illegal immigration.

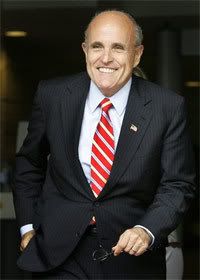

It took prosecutors a while to figure out how to use RICO effectively, but by the mid-1980s, federal investigators in the Southern District of New York were hitting their stride under none other than the crusading United States attorney

Rudy Giuliani, who as the head of the Southern District brought charges in 1985 against the heads of the city’s five dominant Mafia families.

Ever since, S.D.N.Y. prosecutors and F.B.I. agents have been the nation’s gold standard in RICO prosecutions — a fact that makes clear precisely why, after Mr. Cohen’s testimony, President Trump’s greatest legal jeopardy may not be in the investigation by the special counsel, Robert Mueller.

What lawmakers heard Wednesday sounded a lot like a racketeering enterprise: an organization with a few key players and numerous overlapping crimes — not just one conspiracy, but many. Even leaving aside any questions about the Mueller investigation and the 2016 campaign, Mr. Cohen leveled allegations that sounded like bank fraud, charity fraud and tax fraud, as well as hints of insurance fraud, obstruction of justice and suborning perjury.

The parallels between the Mafia and the Trump Organization are more than we might like to admit: After all, Mr. Cohen was labeled a “rat” by President Trump last year for agreeing to cooperate with investigators; interestingly, in the language of crime, “rats” generally aren’t seen as liars. They’re “rats” precisely because they turn state’s evidence and tell the truth, spilling the secrets of a criminal organization.

Mr. Cohen was clear about the rot at the center of his former employer: “Everybody’s job at the Trump Organization is to protect Mr. Trump. Every day most of us knew we were coming and we were going to lie for him about something. That became the norm.”

RICO was precisely designed to catch the godfathers and bosses at the top of these crime syndicates — people a step or two removed from the actual crimes committed, those whose will is made real, even without a direct order.

Exactly, it appears, as Mr. Trump did at the top of his family business: “Mr. Trump did not directly tell me to lie to Congress. That’s not how he operates,” Mr. Cohen said. Mr. Trump, Mr. Cohen said, “doesn’t give orders. He speaks in code. And I understand that code.”

What’s notable about Mr. Cohen’s comments is how they paint a consistent (and credible) pattern of Mr. Trump’s behavior: The former

F.B.I. director James Comey, in testimony nearly two years ago in the wake of his firing, made almost exactly the same point and used almost exactly the same language. Mr. Trump never directly ordered him to drop the Flynn investigation, Mr. Comey said, but he made it all too clear what he wanted — the president isolated Mr. Comey, with no other ears around, and then said he hoped Mr. Comey “can let this go.” As Mr. Comey said, “I took it as, this is what he wants me to do.” He cited in his testimony then the famous example of King Henry II’s saying, “Will no one rid me of this turbulent priest?,” a question that resulted in the murder of that very meddlesome priest, Thomas Becket.

The sheer number and breadth of the investigations into Mr. Trump’s orbit these days indicates how vulnerable the president’s family business would be to just this type of prosecution. In December, I counted 17, and since then, investigators have started an inquiry into undocumented workers at Mr. Trump’s New Jersey golf course, another crime that could be a RICO predicate; Mr. Cohen’s public testimony itself, where he certainly laid out enough evidence and bread crumbs for prosecutors to verify his allegations, mentioned enough criminal activity to build a racketeering case. Moreover, RICO allows prosecutors to wrap 10 years of racketeering activity into a single set of charges, which is to say, almost precisely the length of time — a decade — that Michael Cohen would have unparalleled insight into Mr. Trump’s operations. Similarly, many Mafia cases end up being built on wiretaps — just like, for instance, the perhaps 100 recordings Mr. Cohen says he made of people during his tenure working for Mr. Trump, recordings that federal investigators are surely poring over as part of the 290,000 documents and files they seized in their April raid last year.

Indicting the whole Trump Organization as a “corrupt enterprise” could also help prosecutors address the thorny question of whether the president can be indicted in office; they could lay out a whole pattern of criminal activity, indict numerous players — including perhaps Trump family members — and leave the president himself as a named, unindicted co-conspirator. Such an action would allow investigators to make public all the known activity for Congress and the public to consider as part of impeachment hearings or re-election. It would also activate powerful forfeiture tools for prosecutors that could allow them to seize the Trump Organization’s assets and cut off its income streams.

The irony will be that if federal prosecutors decide to move against President Trump’s empire and family together, he’ll have one man’s model to thank: his own TV lawyer, Rudy Giuliani, who perfected the template to tackle precisely that type of criminal enterprise.

Thanks to

Garrett M. Graff.

in 1986, an informant told the FBI, according to testimony in October of 2007, in Brooklyn state court. But while the late Gambino crime boss

in 1986, an informant told the FBI, according to testimony in October of 2007, in Brooklyn state court. But while the late Gambino crime boss